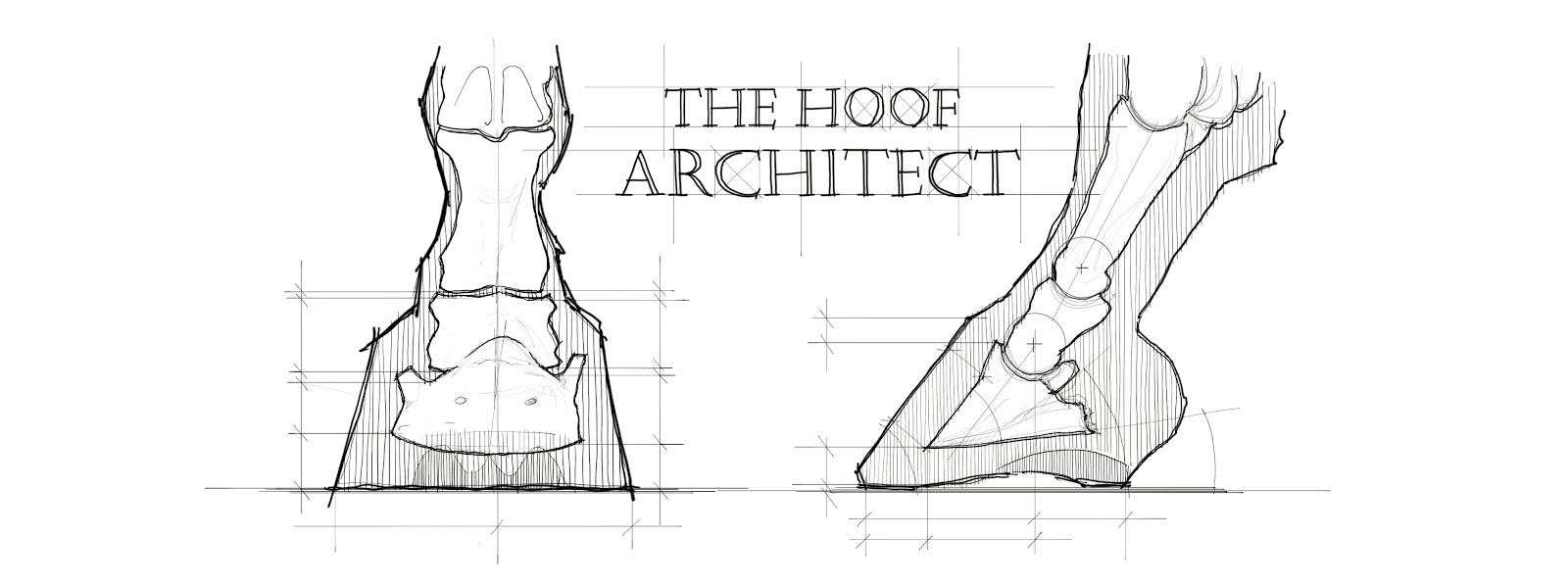

DCA and the Missing Aspects of Dorsopalmar Balance (Part 2 - major conformational and postural aspects creating hoof distortions)

© Ula Krzanowska / The Hoof Architect 2024–2026. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized reproduction, redistribution, adaptation, or derivative works (including redrawn diagrams or similar concepts without attribution) prohibited without written permission.This content, including original observations, biomechanical interpretations, and diagrams, was first publicly presented by the author at the 4th International Congress on Equine Podiatry, Jerez de la Frontera, Spain, May 16–18, 2024.

Unauthorized reproduction, redistribution, adaptation, or derivative works (including redrawn diagrams or similar concepts without attribution) prohibited without written permission.

Introduction

In Part 1. of this article series we analysed these two feet and what differences in load distribution may be responsible for creating them. I presented my understanding of the macro-level hoof capsule distortions based on a simple cube-model analogy. We concluded that answers to some questions likely lie in the biomechanics of the fetlock joint.

This part dives deeper into that topic. I want to make it clear that these are mostly my observations and presentation of my understanding, not conclusions based on precise mathematical calculations.

DCA is a valuable parameter that may provide us with a lot of insight about internal biomechanics of the hoof and of the whole limb. It is not something we want to trim for (we cannot affect it with a trim directly!) but an important guideline for further research as well. This whole material started with me analyzing why different feet have different DCA values and I feel like it has led me to exploring areas I would never think of otherwise.

The Fetlock as a Suspension System

I admit it may be unusual to have a favorite horse body part, but mine remains unchanged: the fetlock joint.

|

| I believe the fetlock joint to be a structure which has the most influence on the hoof capsule shape. |

I want to make it clear: I DO NOT mean that the fetlock joint is more important than the rest of the body in this aspect. Rather, it is my observation that whatever is happening in the rest of the body, before it reaches the hoof, is first converted through the fetlock and affects it in a more or less significant way. For example flexing/pushing forward the knee is going to affect the fetlock very significantly, the same as collapsing of the thoracic sling, decreasing the mobility of the SI region or standing camped under or camped out. Every weight shift is going to affect how the hooves are loaded - but it is going to affect the fetlock, the response of which will decide what biomechanical outcome it has on the hoof.

The fetlock gathers inputs from above, and all compensations influence its biomechanics. It filters and converts vertically transmitted load from the upper body into partially horizontally suspended weight via tendons and ligaments.

The fetlock is a spring, energy container and shock absorber and it significantly differentiates the biomechanics of the equine limb compared to most other species.

It adds a new dimension to the way we look at the hooves.

|

| Unique architecture of the equine distal limb - suspension of the fetlock joint |

I believe its position is absolutely crucial when it comes to the load distribution within the hoof and thus - hoof morphology.

|

| When the suspension of the fetlock fails completely, this is what happens. Photo courtesy: Raul Bras |

Gravity has no mercy and does not select - the fetlock joint is being pulled towards the ground constantly - its suspensory apparatus prevents its hyperextension. Failure of this system leads to its collapse. This can be a result of an acute injury or a slow degeneration process.

Posture and Conformation

It is repeated over and over (also by me) that conformation and posture are the aspects that determine how the hooves are being loaded and how they grow and deform.

What specifically do I mean by conformation and posture in this context?

To me the most important factors we should look at are:

position of the limb,

amount of fetlock extension

phalangeal alignment.

These aspects interact with each other.

Amount of fetlock extension is determined by:

sufficiency of the suspensory apparatus of the fetlock joint (mainly the suspensory ligament and the seamoidean ligaments in the pastern area)

tension and length of the superficial flexor muscle tendon unit

to a lesser degree by the deep flexor muscle unit tension and length

amount of applied load

Phalangeal alignment is determined mainly by:

hoof angulation,

tension of the flexor tendons and ligaments,

amount of applied load,

position of the limb.

This also determines the position of the fetlock joint (the amount of its extension), how much it drops during the stance phase at full load and how much the coffin joint flexes or extends during propulsion and breakover.

Horses can adjust their posture by placing the limb more forward or backward or – according to my observations – by raising the fetlock. Position of the fetlock joint is certainly determined by the tension within the suspensory ligament, flexor tendons and hoof angle, but I commonly observe that some horses must have some active influence on the position of the fetlock. I see that some horses raise their fetlocks (probably to relieve discomfort or pain?) and make it more upright without a change in hoof angulation. I have also seen some of these horses drop the fetlock to its previous position when the problem is resolved or the pain has been taken away. I think this also depends on conformation and that not all horses are able to do that.

DDFT Tension and Fetlock Position as main factors that influence load distribution within the hoof

It is widely accepted that:

more DDFT tension shifts load forward,

less DDFT tension shifts load toward the heels.

I was taught this by Dr. Redden and my observations align with this theory.

However, I believe that on top of that there must be more factors that in my opinion should be considered. In short, I observe that:

the more upright the fetlock, the more load concentrates in the central area,

the lower the fetlock drops, the more load is transferred onto the caudal structures and the toe area, with less load in the centre.

Position of the limb relative to the neutral (vertical towards the ground) position:

Moving the limb forward straightens the fetlock joint and flexes the coffin joint, relaxing the DDFT, lowering the fetlock and shifting weight onto the caudal structures.

Moving the limb backward extends the coffin joint and brings the fetlock up, tensing the DDFT and shifting weight forward and onto the central area depending on the configuration.

|

| Some of my considerations about how change in the position of the limb and position of the fetlock affects load distribution within the hoof. The blue shapes show a conceptual and simplified change in load distribution RELATIVE (not absolute!) to the neutral starting point with the limb vertical and HPA aligned. The red dotted lines show a direction in which the coronary band will follow as a response. |

A collage of different arrangements of phalangeal alignment and limb positions to visualize how weight distribution probably changes – the change is relative to the starting neutral position, not absolute. Increasing or decreasing DDFT tension should shift those graphs forward or backward.

Fetlock position and DCA

After a couple of years of an extensive analysis (including consulting with my building mechanics professor) this is my working theory:

|

| A simplified animation of relative load distribution change associated with fetlock position change. |

The more upright the pastern and the more broken back the DIPJ alignment, the more direct load in the central area of the foot - which includes the navicular bone and central or caudal aspects of P3. This originates from my observations:

horses with upright fetlocks and broken back HPA often have hooves with wide DCA, flat centre and elongated caudal part,

horses with dropped fetlocks and broken forward DIPJ alignment often have narrow DCA, low crushed heels, concave centre and rather steep toes, which would rather bullnose than deform into a flare,

depending on conformation, horses can actively influence fetlock position to some degree – probably by tensing mainly the SDF muscle? – for example as a response to pain or discomfort, which may occur without any change to hoof geometry.

Nuances of Phalangeal Alignment

The industry commonly differentiates between straight, broken forward and broken back phalangeal alignment. But is that really that simple?

First of all, phalangeal alignment and hoof pastern axis (HPA) are not the same thing. Whilst HPA is commonly assessed by the external appearance of the limb, phalangeal alignment is assessed based on x-rays.

|

Source: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/what-your-horse-s-hoof-angle-may-be-telling-you A common way of illustrating 3 types of hoof pastern axis.. A - straight, B - broken forward, C - broken back This is a beautiful drawing and I do not mean to critique it as it serves the general purpose of illustrating what is meant by hoof pastern axis. It should however be specified that it is a simplified approach and this drawing is not anatomically correct - especially the shape of the heels and DCA do not reflect what is happening in real life cases. |

Whilst HPA can indeed be either straight, broken back or broken forward (it is a very ‘rough’ and unprecise parameter though, and can be quite misleading), I find phalangeal alignment to be a much more complicated parameter which is often oversimplified. This leads to loss of important data, which in my opinion should be noticed and taken into account, as they may significantly affect the ultimate outcome on the hoof.

|

| 3 different versions of broken back phalangeal alignment, created by different biomechanical arrangements and creating different load distribution within the hoof. |

Alignment of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) is a very important factor which is often skipped. I observe it to also affect the orientation of the DIPJ.

It makes a difference whether we have broken HPA with a straight (or even flexed, subluxated forward) PIPJ or if PIPJ is broken back: in the first case scenario, the break in alignment is likely to be more pronounced in the DIPJ, while in the second - the DIPK tends to be more aligned.

Ultimately, the coffin joint alignment seems to me to be the most important element of phalangeal alignment when it comes to its outcome on the hoof.

What dictates the alignment of PIPJ?

I believe SDFT tension plays a big part (the higher the tension, the more tendency for the forward subluxation), DDFT tension (the higher, the more tendency for a flexion in PIPJ), efficiency of the sesamoidean ligaments, probably quality of the digital cushion? The list may be longer. What is important, is that I consistently observe that changing hoof geometry often does not affect that in any significant degree - this means we probably do not have that much influence on the phalangeal alignment as we tend to think we do.

|

Broken back hoof pastern axis can look very differently and result in different outcome when it comes to load distribution over the hoof. Usually the more broken back the PIPJ, the less broken back the DIPJ, and this results in different hoof distortion patterns. We must be aware that it is not something we can always influence! Quite often only changing hoof balance is not going to fix it; sometimes it may be not fixable at all. |

DIPJ Alignment, P2–P3 Relationship

The DIPJ alignment refers directly to the angle of the force exerted by P2 on P3. It is a very important element of the puzzle and it depends on multiple factors listed above (DDFT tension, fetlock position, PIPJ alignment, hoof angulation, amount of applied load, etc.).

When we look closely at the DIPJ alignment on different x-rays, we notice that even within the ‘straight HPA’ there can be a big discrepancy between the relationship of P2 and P3. We may have P2 caudally shifted in relation to P3 (common in DDFT laxity cases, after DDFT injuries, after tenotomy), or P2 shifted cranially (common in club feet). In the first case, the weight is going to be shifted caudally in reference to the situation when P2 is acting on the cranial aspect of the articular surface of P3 - which shifts the weight cranially.

|

| The relationship of P2 and P3 should be considered independently of their angular alignment. In DDFT contracture cases it is common to observe dorsal pinching of the joint, which tends to increase with lowering of the hoof angle. When the DDFT does not provide proper suspension, P2 tends to ‘slip’ backward, pressing on the caudal aspect of P3 and sometimes directly onto the navicular bone. |

Influence of Descending Fetlock

When the fetlock drops under load, numerous things happen depending on the specific limb conformation.

As stated in the previous part of the article, the load that goes down onto the hoof is being shared by:

the boney column,

caudal structures compressed by the pastern,

DDFT which provides the suspension to the caudal hoof.

Depending on how low the fetlock drops, the ratio between those aspects is going to change.

|

| Some of the aspects associated with fetlock descent. They will be broken down below. |

Biomechanical Consequences of Descending Fetlock

I have distinguished three main aspects associated with the descending fetlock:

Engagement of DDFT in carrying the load, which transfers the load onto the distal edge of P3 (shifts the weight towards the toe)

Engagement of the DDFT (actually all flexor tendons and SL) in carrying the load. The lower the fetlock, the further back it moves from the base of support. This shifts more weight onto the flexor tendons and SL. The longer the horizontal lever, the more load is being suspended by flexor tendons (SDFT and DDFT). A common belief is that once we unload one of those structures, the others get proportionally more load. However, I see that as a misconception, as the amount of suspended load does not equal the overall weight and is not the same all the time. The lower the fetlock, the further away it is from the base of support, thus its leverage is increased. Therefore, both DDFT, SDFT and SL receive more load, no matter their ratio.

|

The change in base of support - cannon bone relationship with the fetlock drop. Opposing effects of DIPJ flexion and MCJ extension on DDFT tension. |

Opposing Joint Effects

Descending (hyperextending) fetlock tightens the DDFT, simultaneously flexing the DIPJ - relaxing the DDFT. Depending on pastern length, cannon bone length, size of the distal and proximal sesamoid bones and extensor tendon pressure around the DIPJ, descending fetlock may engage the DDFT in carrying the load to different extents.

Contraction vs load vs shortening

Another aspect to consider is the distinction between those 3 aspects.

1. Contraction-driven tension — generated by active contraction of the flexor muscle unit.

2. Elongation-driven tension — resulting from passive stretching of the tendon by external forces, primarily the descending fetlock and the portion of body weight suspended by the digital flexor apparatus.

3. Structural Shortening of the Muscle–Tendon Unit - resulting tension does not originate from active contraction nor from load-induced stretching, but from a permanent shift of the length–tension equilibrium due to congenital or acquired shortening of the DDFT muscle–tendon unit.

|

Too extreme examples here: On the left a case of congenital unaddressed shortening of the DDF tendon-muscle unit; on the right the DDFT is being loaded secondarily due to failure of the suspensory apparatus of the fetlock joint (likely SL and SDFT failure). In both cases the DDFT is under excessive tension, which is the reason for the caudal hoof being lifted off the ground. My practical observations are that the position of the fetlock affects the DDFT tension also in normal feet. |

This distinction is functional rather than purely mechanical. In both situations the tendon experiences longitudinal tensile force, yet the origin of that force - neuromuscular activation versus load-induced strain - leads to different biomechanical consequences within the hoof.

I believe the same refers to the SDF muscle-tendon unit. Horses frequently appear able to increase flexor muscle tone to modify fetlock orientation as a protective strategy. In such cases the SDFT acts primarily as an active stabiliser of the bony column; the tendon is ‘tight’, but not necessarily highly loaded in terms of weight bearing. Clinically this is often associated with a more upright fetlock position and a tendency toward centralisation of load within the hoof capsule.

Contraction-driven tension may occur even in the absence of substantial vertical load.

Elongation-driven tension, in contrast, arises when the fetlock descends relative to the base of support and the pastern functions as a lever. The tendon is then stretched passively by the suspended mass of the limb and trunk. Here the flexors become a structural component of the load-bearing system, sharing weight with each other and with the suspensory ligament. The same magnitude of tensile force therefore reflects true mechanical loading, commonly accompanied by increased compression of the caudal hoof and altered breakover mechanics.

Importantly, tension is not equivalent to load. A tendon may exhibit high tension with minimal weight bearing (contraction-driven), or carry substantial load with comparatively little neuromuscular activation (elongation-driven). In many real limbs both mechanisms coexist; descending of the fetlock can provoke reflex flexor activity, creating a mixed pattern in which the clinical picture cannot be interpreted from ‘tightness’ alone.

A third situation must be considered: congenital or early-acquired shortening of the DDFT/SDFT muscle-tendon unit. In such cases the resting length of the system is structurally reduced and the available range of elongation is limited regardless of neuromuscular activity. The resulting tension does not originate from active contraction nor from load-induced stretching, but from a permanent shift of the length-tension equilibrium.

Functionally this resembles a continuous hypoextension of the DIP joint (in DDFT shortening) or hypoextension of the fetlock joint (in SDFT shortening). The hoof and the limb therefore behave as if dominated by contraction-type mechanics, although the underlying cause is architectural rather than neuromuscular.

Role of Caudal Structures

The more upright the pastern, the less engagement of caudal structures in sharing weight.

Caudal structures (the digital cushion, frog) are mostly placed caudally to P3 - under P2, so they can only actively share the load transferred by the bony column when P2 descends down onto them.

|

| A simplified visual of the relationship of the digital cushion and frog with P3. Only a very tiny part lies underneath P3. |

The digital cushion is connected to the DDFT; when the fetlock goes up, the tendon pulls the cushion up with it – probably this is one of the reasons for their elongation and backward/upward displacement in upright fetlock feet.

When a DDFT contracture is present, it may prevent loading of the caudal hoof - the caudal structures do not meet the ground, instead they get pushed down and forward by the descending fetlock.

When loaded, caudal structures act as a fulcrum for the descending pastern.

Caudal structures act as a 1st class lever fulcrum for the descending pastern, which is counteracted by the DDFT tension.

In simplification:

descending fetlock makes the pastern a lever with caudal structures acting as fulcrum,

longer pastern – longer lever arm,

more forward the caudal structures – longer lever arm,

more rigid caudal structures – greater upward force,

but they have a compression limit and may collapse,

DDFT tension plays an important role in counteracting the upward movement of distal P3 edge which would be a result of the lever mechanics.

Lever Mechanics and Stability

If a force moves the distal part of P2 and the coffin joint upward, why does the hoof not flip up?

Actually, sometimes it does. The lever of the descending fetlock is counteracted by DDFT tension; in some cases this tension is insufficient.

Horses with DDFT laxity, after tenotomy or injury may have the distal hoof lifted off the ground with all load on the heels and very wide DCA.

On the left: horse with a very long pastern but DDFT tension sufficient enough to keep the toe on the ground and balance the backward COP shift. On the right: a hoof with insufficient DDFT tension to counteract the lever of the pastern - the base of support migrated forward exacerbates the problem. The horse was compensating some other issue by flexing the knee, which probably was the reason for decreased DDFT tension.

Some laxity cases can be helped by moving the base of support backward or lowering fulcrum height by trimming heels, but many already have too low angles.

Moving the base of support backward may stabilize the hoof, however it may also cause the distal edge of P3 to act forward and upward against the dorsal wall, creating laminar compression or in time remodeling of P3 – the bullnose shape.

Without sufficient DDFT tension, depending on the location of the last point of support, the lever of the pastern may be considered a 2nd class lever with the fulcrum located somewhere at the lamellar junction of the dorsal wall? (in my opinion not in the COR of DIPJ as there are tensile forces where P3 is being pulled up and the hoof capsule is pulling down) and the caudal structures becoming compressed by the descending bones and the shoe/ground (a nut-cracker effect). With a failure of fetlock suspension the lever may load the extensor tendon and SL branches – probably why some DSLD horses benefit from raising heels and extending the base back.

DDFT tension is also going to affect how feet respond to open heel shoes. If it provides strong enough suspension, the caudal failure (downward displacement of the frog and digital cushion) is unlikely to take place. That is why club feet do not tend to show typical frog prolapse even after years of being shod without frog support.

Shoes, Suspension, and Caudal Collapse

Open-heel shoes remove part of support for this fulcrum (frog and digital cushion); the descending pastern pushes them down and shifts their position relative to P3 and the dorsal part of the hoof. Lower descent without support increases pressure on palmar processes and may lead to further morphological changes.

The quality of the caudal structures is extremely important, but let's be realistic - without proper suspension of the DDFT, the compression in the caudal hoof gets too significant and the soft tissues have to respond to that. In my observation and understanding, the collapsed shape of the caudal structures is more often a result of the limb conformation/posture that determine load distribution within the hoof, than the primary reason for problems with maintaining proper hoof shape and angulation - which problems also stem from the load distribution due to conformation/posture. For example, the toughest digital cushion is not likely to maintain its shape and position after the horse undergoes a DDFT rupture.

Horses whose fetlocks stay upright are less prone to frog prolapse but tend to get different types of distortion.

DDFT Tension and Bullnose

Two cases of DDFT failure show how upward acting P3 creates bullnose. Bullnose is very commonly observed in DDFT laxity cases. Note that this is a very different bullnose pattern to that observed in club feet.

The downward pull of the dorsal aspect of the hoof capsule against the upward pulling distal edge of the coffin bone may lead to this characteristic stretch and elongation of the terminal papillae leading to thickening of the solar corium. Due to less compression in that area, they also grow a lot of horn and develop deep concavity in the dorsal area. Those hooves usually do not flare at the toe no matter how long the toe – this also likely has to do with their biomechanics of breakover, which is affected by DDFT and SDFT tension.

Caudal structures can only take so much load and they may reach the point when they collapse, get shifted backwards and up in reference to P3, and the fulcrum moves to the area under palmar processes.

X-rays illustrating the problem - from compressed distal laminae to severe bullnose.

Although commonly associated with NPA feet, bullnose is not only present in negative palmar angle hooves and I do not believe it to be the direct consequence of NPA, but rather both bullnose and NPA to be a consequence of the baseline mechanical situation of the limb, associated with lower DDFT tension. I generally observe bullnose in limbs where fetlocks drop low and with longer fetlocks.

Probably more factors are involved - posture and moving pattern also likely play a role in determining whether the bone is going to develop a bullnose and how much. I commonly observe the hind limbs to exhibit that to a larger degree than fronts and I believe it has to do with the fact that they tend to show more flexion and less extension of the DIPJ during locomotion.

COR location and DDFT Tension

A little digression - I observe a correlation between DDFT tension and COR location on the lateral view.

In more lax DDFT hooves, usually COR is located a little further back than distal ⅓ of the coronary band. With a tight DDFT it tends to be closer to the dorsal wall than ⅓.

This situation further puts the caudal structures under more load in cases of insufficient DDFT tension.

Forward Push of Descending Fetlock

Another factor responsible for transferring weight dorsally is the forward push of the descending fetlock.

Fetlock drops down and back – friction prevents the hoof from sliding forward (depending on surface), which creates compression of P1 and P2 and forward push exerted by P2 on the extensor process of P3. This likely transfers some more load towards the dorsal aspect of P3 and may additionally engage the extensor tendon and extensor branches of SL.

Forward push of the descending fetlock. Backward movement of the dropping fetlock together with ground friction create compression in the pastern, pushing forward on the extensor process of P3 and extensor tender insertion area.

This again highly depends on conformation, balance, movement pattern, stride length, gait and speed, and front and hind limbs show it to different degrees. It may also contribute to bullnose development.

Summary

All of the aspects described above (and probably many more) work together, creating specific hoof morphologies and shapes. Biomechanics of the equine distal limb is one extremely complex topic, with many aspects contributing to different forces exerted onto the hoof. The nuances of phalangeal alignment matter, as well as details of locomotion patterns. Conformation and postural adaptations both seem to be playing roles here, including the shapes of the bones, lengths, ratios and elasticity of tendons and ligaments, muscle tension, fascia, body weight and more.

A very short takeaway from this part:

broken back alignment of DIPJ with upright pasterns tends to go hand in hand with central overload and wider than normal DCA values,

broken forward alignment of DIPJ and dropped pasterns tend to go hand in hand with overload of caudal and/or cranial aspect of the hoof and narrow DCA values,

more or less straight alignment tends to go hand in hand with normal (100-110 for fronts, 95-105 for hinds) DCA values and generally good looking, evenly loaded feet.

There are many nuances to that; breakover patterns lay a big role too - this will be covered in the following parts.

|

| A table showing a simplified tendency to pattern of distortion and DCA in feet with corresponding phalangeal alignment. Just some of the possibilities. |

In the following parts I am going to dive deeper into internal changes associated with different DCA values, what we can read on their x-rays and into biomechanics of breakover which may affect the DCA measurement. Stay tuned.

References:

Sapone M, et al. Fetlock Joint Angle Pattern and Range of Motion Quantification... Vet Sci. 2022;9(9):456. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9502055/

The Truth about Hoof Pastern Axis. The Equine Documentalist. 2020. https://www.theequinedocumentalist.com/the-truth-about-hoof-pastern-axis

Logie C, et al. Investigating Associations between Horse Hoof Conformation... Animals. 2024;14(18):2697. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11444133/

Denoix JM. Understanding the Biomechanics of the Horse's Fetlock Joint. EquiManagement. 2025. https://equimanagement.com/research-medical/sports-medicine/understanding-the-biomechanics-of-the-horses-fetlock-joint

Bramlage LR. (Quoted in) JAVMA News. 2010;236(3):257. https://avmajournals.avma.org/view/journals/javma/236/3/javma.236.3.257.xml

South Shore Equine Clinic. Excessive DDFT Tension. https://www.ssequineclinic.com/equine-health-topics/excessive-ddft-tension

American Farriers Journal. Measurement of the Hoof-Pastern Axis... 2016. https://www.americanfarriers.com/articles/8812-measurement-of-the-hoof-pastern-axis-for-foot-management

American Farriers Journal. Understanding the Equine Digital Cushion. 2025. https://www.americanfarriers.com/articles/15218-understanding-the-equine-digital-cushion

O'Grady SE. Physiological Horseshoeing - An Overview. http://www.equipodiatry.com/news/articles/physshoehtm

Redden RF. Recognizing Various Grades of the Club Foot Syndrome. NANRIC. 2012. https://www.nanric.com/post/recognizing-various-grades-of-the-club-foot-syndrome

Schramme MC. Deep digital flexor tendinopathy in the foot. Equine Vet Educ. 2011. https://beva.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.2042-3292.2011.00235.x

Comments

Post a Comment