Rotation Rotation Rotation

We keep reading about rotation everywhere. It is being brought up when talking about laminitis, about trimming, about DDFT tension. Interestingly, when we analyse closely, we realise that people use that term to describe a couple of totally different parameters of the hoof: some people refer to the palmar/plantar angle, some to the phalangeal alignment, and some to the P3/dorsal wall alignment.

So what is rotation, what does this term really refer to?

Despite this word being used so commonly, there is so much chaos and misunderstanding surrounding it. And those misunderstandings feed even more misunderstandings and create more chaos. So let's first break it down.

Although I have my opinions on that topic and personally find points 1 and 2 to be an inappropriate use of the term ‘rotation’, I will try to objectively break them all down and present my point of view.

First of all, what does the word ‘rotation’ mean?

By definition, ROTATION means:

‘the action of rotating about an axis or centre’

The angle of rotation is measured in degrees or radians to indicate the amount of turn.

To be able to measure the angle of rotation, a baseline (initial position) must be known, as well as the terminal position.

Considering the above, when we say something is ‘rotated’ it means that it has taken the action of rotating from some default, baseline position. This baseline position should be defined in order to determine whether rotation has occurred and to reliably measure it.

1. 'Rotation' meaning hyperpositive PA/PLA

Some people describe the coffin bone sitting at a positive/hyperpositive PA/PLA in the hoof capsule as 'rotated'.

First of all, there is no set P3-ground alignment value that is correct for all horses, so there is no set default value that we could refer our measurement to.

Although there are many different approaches to what ideal PA/PLA should be: there are people that advocate for ground parallel P3, some define a range of PA/PLA values that are generally considered correct (like 2-8, 3-5 degrees), others do not define any accepted range but just aim for whatever is needed to achieve straight HPA. In my opinion 'correct' PA/PLA is very individual and may change over time. For some cases 5 degrees may be too low or impossible to achieve (in some club feet for example) and for others the same value will be too much and considered as ‘hyperpositive’.

Thus the word ‘hyperpositive’ when it comes to PA/PLA value is also used subjectively - there is no objective way to determine the threshold from which ‘positive’ turns into ‘hyperpositive’.

The most common way of assessing PA/PLA is just measuring it in degrees in reference to the ground plane. It can also be objectively classified as either positive, negative or neutral, we can subjectively call it low or high. Why call it 'rotated'?

lowering heel height or adding depth at the toe is going to decrease PA/PLA value,

removing depth at the toe or adding height at the heels is going to increase PA/PLA value.

PA/PLA changes over time in most horses due to uneven growth and wear and obviously is affected by farrier’s manipulation. It is not a constant value which is assigned to a specific leg or a specific horse.

if a horse grows more toe than heels and/or wears the heels more than the toe, PA/PLA will decrease over time,

if a horse grows more heels than toe and/or wears more toe than heels, PA/PLA will increase over time.

PA/PLA can also slightly change over time without adding or removing horn, due to shift of the internal structures of the hoof, which is usually more subtle and takes more time (hoof capsule is a viscoelastic structure, it deforms dynamically and adapts to load). If a horse changes posture, the load distribution within the hoof may change and certain areas may lose suspension and start to collapse. If it is the central/caudal area, PA/PLA may slowly decrease without external manipulation of the hoof capsule and its value may get lower despite unchanged height at the heels (heels and side walls get pushed up in reference to the bone). This commonly happens in open heel shoes in horses that do not have sufficient DDFT suspension to counteract the caudal hoof prolapse. The opposite scenario - when the cranial area of the sole loses its suspension is what tends to happen in the early stage of laminitis.

(In laminitis also the posture and conformation of the limb plays a big role, as it determines which area of the hoof is going to get most damage: that is why some of the horses will rotate and some sink, some will sink medially or laterally depending on the conformation).

This early laminitic rotational P3 displacement means that PA will increase due to the collapse of the supension of the dorsal aspect of P3. This PA increase may not seem very dramatic at first sight: often it is not more than couple of degrees; however in most cases it comes along with some degree of sinking - early laminitic rotation is sometimes assumed to be a kind of non-uniform sinking, where the cranial part of the bone sinks more than caudal. If this happens, it always comes along with the rotation between the dorsal wall and dorsal edge of P3 - this will be discussed more extensively in point 3a. In such case scenario, if we know the PA/PLA value before laminitis, we could reliably measure how much it has increased and thus calling it P3 rotation angle value would seem more valid to me.

Moreover, what usually follows the acute laminitic episode is an uneven hoof growth - it is very common for those cases to stop/slow down growing at the toe and continue to grow heels, which directly affects the PA/PLA value and leads to its gradual increase over time if unattended.

|

| A laminitic hoof 8 weeks after the insult - note no growth at the dorsal wall and growth present at the heels. |

Anyway, since in vast majority of cases the trim/shoeing package will directly influence PA/PLA value, I advocate to stop calling high PA/PLA value ‘rotation’ and just call it high PA/PLA value, steep PA/PLA or alike. The word ‘rotation’ is usually associated with laminitis and although abnormally hight PA/PLA is commonly present in neglected laminitic hooves, so many horses with high PA/PLA value do not have any laminitic issues and their steep P3-ground alignment has nothing to do with laminitis.

To sum up why I suggest to not call high PA/PLA rotation:

no set default correct PA/PLA value to refer to with the measurment of the 'rotation' angle

PA/PLA is directly influenced by trimming/shoeing package in most cases, thus can be manipulated easily and by itself it is not a prognostic for the severity of the damage or for the outcome

although high PA/PLA is commonly found in chronic laminitic cases, it is not a parameter directly related to laminitis and can be found in many healthy hooves

2. 'Rotation' meaning broken forward HPA/flexed coffin joint

When the dorsal edge of P3 is more steep in reference to the ground than long axis of the pastern (some people measure P2 axis, some measure P1 and other draw a line between COR of DIPJ and MCJ) it is being called ‘broken forward HPA’ or ‘broken forward phalangeal alignment’. Phalangeal alignment and HPA (hoof-pastern axis) are not exactly the same, they are commonly used interchangeably - which is also not precisely correct but in this article I will not differenciate between those 2 and use those terms interchangably (sorry). What people like to particularly focus on in laminitic cases is the flexion of the coffin joint, which is very commonly called ‘bone rotation’.

I have an impression that people seem to overfocus on phalangeal alignment on x-rays of laminitic horses, almost taking it as something fixed or difficult to change in a certain horse, not understanding or forgetting that:

we usually don’t know how the HPA was aligned before laminitis thus have no baseline for the measurement of this ‘rotation’ (most horses do not have straight HPA to start with!)

HPA/phalangeal alignment is usually affected by PA/PLA (not linearly though)

phalanges are connected with hinge joints (DIPJ and PIPJ) which means they articulate and change alignment with every change of horses posture and with every weight shift.

If we don’t know how the horse was standing when the x-rays were taken, we should approach assessing phalangeal alignment with a big dose of caution.

What is also very important to remember is that HPA is affected by both PA/PLA AND position of the fetlock and pastern.

when there is more load on the limb, the fetlock will drop lower, which will affect the phalangeal alignment

when there is less load on the limb, the fetlock may come up, which will affect the phalangeal alignment

when the limb is moved forward, the fetlock will drop lower, which will affect the phalangeal alignment

when the limb is moved backward, the fetlock may come up, which will affect the phalangeal alignment

In most cases lowering the PA/PLA will affect the HPA/phalangeal alignment in the direction of breaking it back and vice versa.

As explained above, HPA - as the name goes, depends as much on the HOOF as on the PASTERN position, so:

we may have pretty low PA/PLA and a very low fetlock and have broken forward HPA/flexed coffin joint

we may have very high PA/PLA and very upright fetlock and have a straight or broken back HPA/straight or extended coffin joint

This is such a dynamic parameter, affected by so many factors, most of which are unrelated to laminitis. And yes, it is common for chronic, long term laminitic cases to have broken forward HPA/flexed coffin joint, for 2 main reasons:

- neglect: not correcting the distorted growth, letting the heels get higher and higher whilst the toe growth stays compromised and cannot catch up

- DDF muscle contracture due to pain, sometimes called a ‘cringe’ response, which occurs in some percentage of chronic laminitic horses and limits the range of coffin joint extension

The first option is probably much more common and pretty easy to correct as long as the normal range of extension of the DIPJ is still preserved and as long as we are talking about a case that is stabilised and not in an acute phase of laminitis. Just trim the heels, add depth at the toe when needed - voila, ‘derotated’. However, long term consequences of our actions should always be considered, as they highly depend on a case - for some cases just trimming the heels down may be beneficial but in some it may create immediate or long term trouble without additional support.

Digression.

As I already mentioned, if only the range of motion of the DIPJ is still normal, it is very easy to manipulate PA/PLA as well as to correct broken forward HPA or ‘rotation’ with just a trim. However, getting the hoof trimmed to specific parameters and getting specific phalangeal alignment on the specific x-ray is not a guarantee of a successful outcome nor a prognostic factor in laminitis recovery. It is what happens after that correction what determines if the recovery is going in the right direction:

Is the horse gaining, or losing sole depth?

Is the dorsal wall growing at all?

If the dorsal wall is growing, is it growing out better connected, or is it getting more and more concave and compressed at the coronary band?

Is the toe:heel growth ratio getting more balanced, or do we need to constantly chase the heels which grow like crazy?

We also need to remember, that even though we can get more favourable PA/HPA alignment with trimming/shoeing, but the growth rate remains disturbed, the PA/PLA will soon increase and HPA will get broken forward again. Getting the hoof to match specific parameters is not a permanent fix.

The second option is probably (luckily!) less common (according to my observations it is most common in neglected ponies), but a much more difficult case scenario. In those cases the broken forward HPA related to hypoextension of the coffin joint - AKA ‘bone rotation’ - is actually permanent: alignment of the phalanges of course is still dynamic and depends on the posture and amount of load on the limb, but the range of coffin joint extension is limited due to abnormal tension created by the contracted/atrophied deep flexor muscle. So in such a case, even if we trim the heels, the PA may not change and the alignment of P3 and P2 may stay ‘rotated’.

If the DDF muscle has contracted due to pain and it has became chronic, there are no known methods (at least to my knowledge) of reversing that situation non-invasively. Many tries have been made with physiotherapy as well as even with botulin injections into the contracted/atrophied muscle but according to my current knowledge, they do not yield sustainable results. Excessive DDFT tension is very detrimental even for the healthy hoof by dramatically shifting the weight onto the toe, but with a laminitic one it is just an unforgiving force that often undermines any attempts to help such horse and leads to very fast bone deterioration and euthanasia. After trimming the heels in such a case, they will just float in the air and all the load will be placed on the toe. It is very painful for the horse and we should not make them stand on such a hoof without proper support under the heels. The only successful recovery of such cases I have ever experienced, witnessed or heard of was with the use of tenotomy - a procedure which basically allows the horse to extend the coffin joint again, put the floating heels back on the ground and shift the weight caudally, off the P3 tip. I may write about it more at some other time. (BTW, if anybody has a documented case of a successful recovery of a laminitic horse with DDF muscle contracture without tenotomy, I really want to see it.)

Similar clinical presentation may occur if a horse with a congenital or aquired club foot develops laminitis. If such a horse had had a limited range of DIPJ extension even before laminitic episode, it is likely to exacerbate the laminitic damage significantly - in many club footed hooves the heels will float off the ground after lowering beyond a certain point. In this case it is often not the muscle contracture though, but too short distance between the P3 insertion and check ligament of the DDFT.

Before trimming the super tall heels of such a laminitic horse, it is best to check until which point the heels will still touch the ground to assess if the DDFT contracture is involved.

To sum up why I suggest to not call broken forward HPA rotation:

no baseline value to refer to - most horses do not present a straight HPA before laminitis

HPA is usually indirectly influenced by trimming/shoeing package

HPA is directly influenced by horses posture, limb placement, weight and by the efficiency of suspension of the fetlock joint

although broken forward HPA is commonly found in chronic laminitic cases, it is not a parameter directly related to laminitis and can be found also for example in club feet or in horses with DSLD.

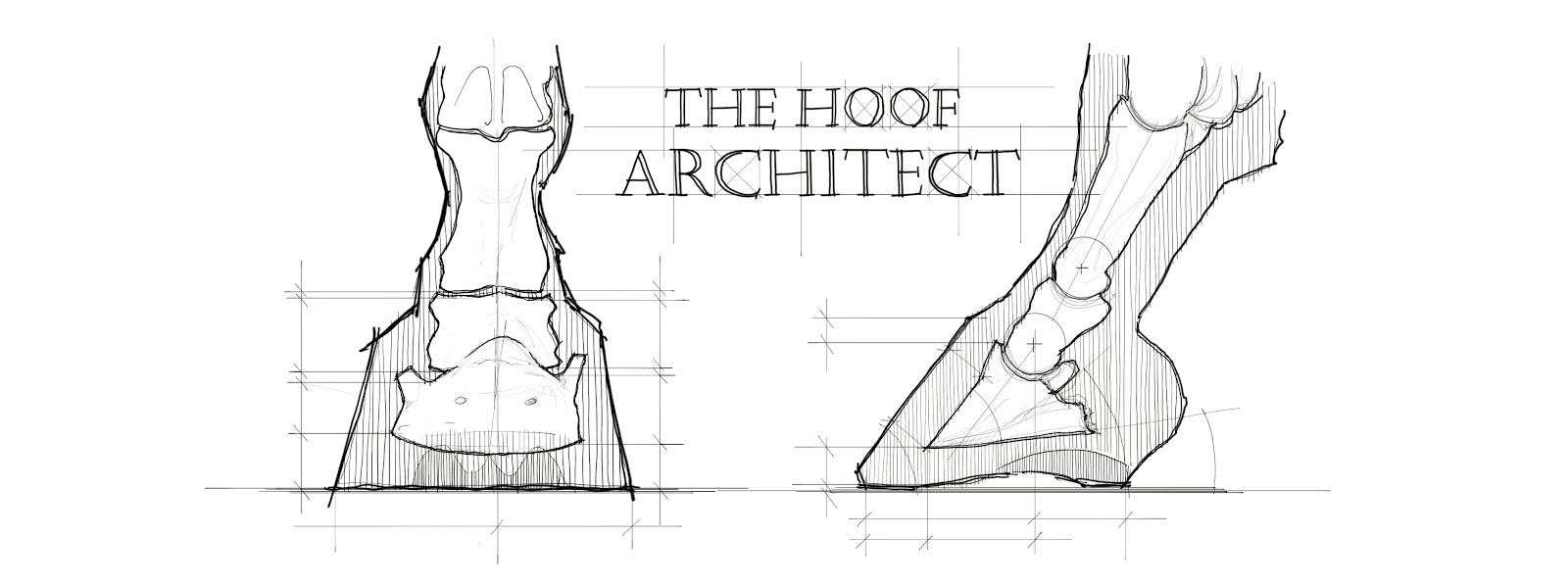

3. Rotation meaning misalignment between the dorsal edge of P3 and dorsal hoof wall

Finally this is what I find to be the ‘proper’ use of the word rotation: rotation referring to the angle between the dorsal hoof wall and dorsal edge of P3. In a healthy hoof they should be parallel to each other, so the rotation angle value should be 0*. Something to be considered however, is that laminar corium has also some elasticity, which means that those measurements can be burdened with error up to 3-5 degrees (Redden).

*It is important to be aware that not only laminitis can lead to those 2 parameters being misaligned! Rotation is not pathognomonic for laminitis.

- Still, this is a fairly straightforward measurement with a set baseline, which is 0 degrees.

- It is also not affected directly by trimming, shoeing, limb position or weight placed on the limb.

Once the wall is rotated away from P3 (or P3 rotated away from the hoof wall - principle of relativity: if one thing moves in reference to the other, the other moves in reference to the first one!) it will not derotate back no matter what happens to the foot or the leg (with the exception of the mentioned few degrees of elasticity that laminar corium has). If we want to get rid of this type of rotation, the only way to get that done is to grow a new better connected hoof capsule. It is not always possible though, depending on the amount of damage.

Of course the rotated wall can be rasped away, but this will still be visible in the x-ray (for example by tracking the DE line) as well as with the naked eye - rasping the rotated wall away will expose the internal layers of the wall and the laminar wedge (see the graphic on the bottom of the article).

The angle of misalignment between the dorsal hoof wall and the dorsal edge of P3 is an important parameter informing about the severity of the disease and about the prognostics.

Great! ...

There is more to it, though.

As straightforward as it seems, misalignment of the dorsal wall and dorsal edge of P3 can be of 2 very different natures, with 2 very different mechanisms to cause it and 2 very different sets of risks and needs.

First one is the early laminitic displacement caused by the failure of P3 suspension in the hoof capsule (SADP) and the second one is the distortion caused by long term disrupted growth due to the damage caused by the initial laminitic insult.

I feel like a very large part of the social media controversy surrounding the topic of rotation is due to not distinguishing those 2 situations from each other. The DDFT pull, lever forces, heel height discussions very often focus on the second case scenario - the chronic capsular distortion caused by disrupted growth due to the past laminitic insult, which is very different from the first case scenario, when internal damage happens inside a previously healthy hoof capsule. Although at the first sight in the x-ray those 2 situations may seem similar, they are not alike at all. It is also much more common to come across the chronic and not the ‘fresh’ ones in social media posts as well as in real life - the early stage I talk about usually lasts for just a few months and the chronic long term one often for the rest of the horses life.

3a. Rotation due to early laminitic displacement caused by the failure of P3 suspension in the hoof capsule (SADP)

This is what happens when acute laminitis enters the so called ‘chronic’ stage - the damaged laminae start to fail and P3 slowly starts to displace inside the hoof capsule. Depending on the conformation of the limb and the severity of the insult it can have different nature: horses with flat foot conformation and very upright pasterns tend to sink more evenly, hooves that belong to limbs with more DDFT tension, that were more upright before the insult, tend to sink more in the cranial part - which means that the more severe downward displacement takes place at the toe. So P3 literally rotates and the axis of rotation is located somewhere around the palmar processes. The caudal part of the bone stays where it was, whilst the cranial sinks down. The early laminitic rotation is always coupled with some degree of sinking.

In such a case, the horn capsule that we see is still the one that had been grown when the hoof was still healthy: in many cases the dorsal wall is straight and strong, without pronounced growth rings or any signs of distorted growth. The thickness of the wall is normal, the shape of the horn aspect of the coronary groove is normal. The caudal part: heels, digital cushion, bars, frog - they also have their normal appearance. If the hoof was of a normal to low heel conformation, the heel height is also normal to low. The white line often also is of normal width without any signs of stretching - yet. Often the only external tell tale signs of laminitis are the increasing convex ridge on the sole just in front of the frog apex followed by excessive exfoliation of the sole in that area, and the look of the dorsal coronary band: the edge of the wall becomes sharp and an indentation forms just next to it. Since the soft tissue connected with the bone (including the skin) gets pulled into the horn capsule with it, the hair right next to the coronary band changes direction and takes up the ‘angry hair’ appearance. These signs can become apparent from over a couple of weeks since the initial insult to just couple of days in the most severe cases, which obviously is a very bad prognostic.

So basically when looking at such a hoof, an inexperienced person may not realise something is wrong, as we see a capsule that had been grown by a healthy undamaged corium*. Laminitic changes can be much more easily spotted on the x-rays.

*This refers mostly to the cases when the laminitic trigger was something sudden and not long term, like sepsis, retained placenta, steroid injection etc. In hyperinsulinemia related cases it is common that the acute laminitic episode follows a long term sublinical laminitis and in such case the hoof capsule may have been showing some mild laminitic signs also before. It is also possible for chronic cases to have new bouts of laminitis (some people call them ‘acute on chronic’) and in such case we may have a combination of long term chronic and new 'fresh' distortion.

|

| The same hoof and its adjacent x-ray taken about a week later. |

X-ray of such an early laminitic hoof will often show an ‘old’ position of the walls and heels with the P3 not matching its previous position. It is especially evident in the hooves where the horse was shod before, as the sole prolapse does not affect the position of the hoof on the ground. As said before, the shape and thickness of the wall will be straight and normal with a clear, straight DE line. The coronary band will sometimes show very characteristic wrinkles. The heels will be of the same height they were just before the episode. The extensor process of P3 will no longer match its adjacent shape if the coronary groove and present downward displacement.

What usually follows the initial laminitic P3 displacement is a period of no wall growth or growth directed horizontally due to coronary papillae displacement. This horizontal growth causes the wall to ‘grow in’ into the corium, simultaneously ‘growing away’ which often results in the very characteristic ‘shelf’ combined with an air gap forming right next to the old wall DE line. When new better connected growth follows, this shelf and air gap grow down.

My understanding is that the presence of this air gap could be used to determine the recent occurrence of the acute laminitic insult and allow for distinguishing it from the long term chronic one - I don’t know if anybody had confirmed it, though.

Usually in such a hoof the P3 edge is still intact and sharp and the lamellar connection severely destabilised - this is the stage where indeed lowering the heels or keeping the leverage at the toe can contribute to the solar penetration (it may happen also without it obviously) and when proper mechanics can stop or significantly limit the amount of internal damage happening. The internal damage at this stage due to the bone displacement is determining the future prognosis for the horse.

In such a case, if there has been no rotation before the laminitic episode, the angle of rotation between the dorsal wall and dorsal edge of P3 will be equal to the angle of rotation of P3 against the ground - this means that if we have for example 7 degrees of rotation between the dorsal wall and the now displaced dorsal edge of P3, the palmar angle of this hoof has also increased by 7 degrees.

By watching the wall just below the coronary band we can track when the new growth after the laminitic insult comes in (usually at the heel area it starts growing sooner and grows faster than the toe) and after that point the distortion of the hoof capsule starts to be partially the effect of the distorted growth.

3b. Rotation caused by long term disrupted growth due to the damage caused by the initial laminitic insult.

Displacement of P3 during the initial laminitic episode creates a lot of the internal tissue damage, including the coronary and solar corium, lamellae and blood vessels. Displaced coronary papillae start producing wall at different direction (away from the bone, not parallel to it). Compression and damage of blood vessels in the toe area makes it grow slower than in the heels, which additionally contributes to the dorsal wall becoming distorted away from the bone. Damaged laminae start to produce the ‘repair’ kind of horn material, which creates the lamellar wedge that fills in the space between the wall and the bone and when growing down shows up as wide, stretched white line.

The growing wall usually does not have the healthy appearance, but rather the typical 'laminitic' one with pronounced growth rings, waves and bumps and often a concave, dished shape. Growth rings become wider at the heels than at the toe, which means that in the same amount of time we have more height increase at the heels than at the toe. Thus, such a hoof will increase in PA over time if not corrected frequently, creating a really common laminitic hoof shape with high heels, coronary band dropping down in front, dished dorsal wall and higher and higher PA.

I do not however suggest calling this increase of PA ‘rotation’ - as explained in point 2. of this article, it is just a result of more horn capsule depth being produced at the heels than at the toe and in most cases can be easily corrected by trimming/shoeing.

In the x-ray of such a hoof the dorsal wall will usually be thicker than normal, convex and showing bumps related to the pronounced growth rings. The DE line tends to be more blurry and more difficult to locate. The coronary groove will be more stretched vertically (thus producing a thicker wall), but it will better correspond with the indentation just below the extensor process of P3. The coronary band in the center of the dorsal wall may be pushed down by the extension of the pastern, having a dropping down appearance and possibly making the CE measurement possibly not so reliable (in the toe quarters it will be higher). The sole in such cases will often be flat and lack depth and concavity and correspond with an eroded tip of P3. P3 will also commonly lack more and more mass and/or have a more pronounced ski tip. The back of such hoof will be pushed down and forward by the pastern descending onto the high heels, giving the heel bulbs a rounded appearance. Due to this distortion, when lowering the heels you may hit blood on the frog and still have quite a lot of depth at the heel buttresses.

When left unattended, such a hoof will grow higher and higher at the heels and more and more forward at the dorsal wall. Although lowering the heels increases the DDFT tension, in such hoof it is unlikely to lead to solar penetration as:

1. the hoof capsule has already stabilised by this point after the initial insult,

2. the heels are often excessively high and after lowering them to the physiological height the DDFT tension does not get excessive (unless there is a DDFT contracture)

3. by this point the P3 had usually already lost its sharp edge and became more flattened and rounded from the bottom

If we however lower the heels to the point of the DDFT tension excesively increasing, the following symptoms often occur:

heel to toe growth ratio becomes more disrupted making the heels grow even faster

the sole may start to lose more and more depth

the bone may start degenerating faster and faster, blowing abscesses and losing mass

the horse may become more painful to unwilling to place any weight on the limb, especially when the heels get lowered beyond the point when they no longer touch the ground.

I do not want to be misunderstood: I DON'T believe we should NOT lower the heels in those cases - I think it is absolutely necessary to get them down to bring the weightbearing surface back and to prevent the hoof capsule distortion from exacerbating. However, we have to asses every case individually and be aware of the possible consequences of every action we take. Some cases will need additional mechanical support to recover, and for some even that will not be enough. We have to also remember that the palmar processes of P3 need proper sole protection and should avoid overtrimming the heels.

Many people observe a tendency that flat feet generally are less prone to rotation in laminitis - but be careful not to confuse correlation with causation. We should rather think about why they are flat in the first place (less DDFT tension?) and how different conformations predispose horses to the damage occuring in specific areas of the hoof. It is not random that one limb usually exhibits more rotation than the other and definitely it is not just due to the way it is being trimmed.

For the ease of comparison, let's also put the previous collages next to each other:

|

|

Summary

So my suggestion:

Couple more illustrations that may help understand the topic:

|

Special thanks to dr Christoph von Horst, Ramon Batalla DVM and Lindsey Field for allowing me to use their materials to make illustrations for this article.

Comments

Post a Comment